Warehouse & Logistics News is proud to bring you the fiftyfirst instalment in our exclusive series on the history of the fork lift truck, the machine that over the decades has revolutionised the face of materials handling around the world. Our series has now reached its half-century in terms of the episodes we’ve published so far, so we’re celebrating reaching a major milestone. And there’s still plenty of the story to come.

Warehouse & Logistics News is proud to bring you the fiftyfirst instalment in our exclusive series on the history of the fork lift truck, the machine that over the decades has revolutionised the face of materials handling around the world. Our series has now reached its half-century in terms of the episodes we’ve published so far, so we’re celebrating reaching a major milestone. And there’s still plenty of the story to come.

Our writer is James Brindley, an acknowledged authority on fork lift trucks. James’s distinguished career has involved engineering and management roles with BT Rolatruc and serving as a Director of the Fork Lift Truck Association, before he set up the National Fork Truck Heritage Centre in 2004 as Britain’s first such collection open to the public.

The Heritage Centre continues to need your support in 2010, and if you or your company would like to help in any way, you can contact James on the number below. Now sit back and enjoy the latest part of this fascinating series.

Episode 51: 1966 continued – Men versus machines at the docks

Continuing with 1966 and the theme of fork lift trucks working on ships and docks, we come to a time when the mechanisation of work came into conflict between the dockers and indirectly the government. It had been muted for quite a number of years that inefficiency and congestion at the docks were prejudicing our export trade and increasing our import costs. The root cause was recognised by many to be the fault of outdated and outmoded handling methods, and to a large extent this was true. However the problem of handling could not be tackled in isolation as at the time the relationship between the dockers and the employers was very strained, to say the least.

Continuing with 1966 and the theme of fork lift trucks working on ships and docks, we come to a time when the mechanisation of work came into conflict between the dockers and indirectly the government. It had been muted for quite a number of years that inefficiency and congestion at the docks were prejudicing our export trade and increasing our import costs. The root cause was recognised by many to be the fault of outdated and outmoded handling methods, and to a large extent this was true. However the problem of handling could not be tackled in isolation as at the time the relationship between the dockers and the employers was very strained, to say the least.

In an attempt to resolve this situation the government of the day appointed Lord Devlin to make recommendations. The Devlin report stressed that it was impossible to have efficient mechanisation against a background of casual labour. His main proposal therefore, which was greeted enthusiastically by Government, employers and trade unions alike, was the decasualisation of dock labour. Although the report was accepted as a major step forward by the unions, it was seen as a danger by the dockers themselves, who sensed that this was a way for the employers to get more work out of them. As in the years gone by they saw little protection from the unions themselves and led by militant action groups were quite used to taking things into their own hands: Since 1960, of the 421 strikes in the docks 410 were unofficial. The final recommendation by Devlin therefore was that the government should intervene directly to ensure that any agreed efficiency plan would not be wrecked by a minority of troublemakers. The suggestion here was to break any unofficial strikes by the intervention of the armed forces. Even so, with the labour element put to one side, efficiency could still only be achieved if British industry as a whole altered its presentation of packaged goods at the ports. Likewise the country’s imports, where possible, would have to be shipped in a similar manner. This would involve major alterations to ship design so that palletized unit loads could be handled by mechanical means.

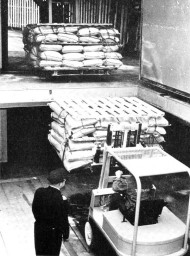

The photo shows a forklift truck working in a hold that has been designed with side ports for loading and discharging this type of pallet. Some ships of the Fred Olsen Line, a pioneer in this type of handling, were already able to handle such goods in most mainland European ports but in most British ports the dockers still manually loaded and unloaded packaged goods as individual items using a load board and slings.

In an attempt to bypass the delays caused by manual loading, some manufacturers opted for containerisation or roll-on, roll-off operations, but at this time there were only a limited number of British ports that could handle this type of freight. Although still behind most other countries in modernizing, one of these facilities for roll-on, roll-off traffic was now available at Hull docks. As for the use of mechanisation, a new wharf was now nearing completion at Millwall docks to handle palletised goods through ship side ports. This new facility was being built by the Port of London Authority for the sole use of the Olsen Line.

In general, from this approximate time, most British ports were starting to follow the lead of the shipping Lines and increasing their efforts to accommodate the new techniques. As a result new docking facilities were well on the way to being built around the country. For their part in modernisation the National Dock Labour Board were now running fork lift and platform truck training schools at London, Liverpool, Hull, Southampton Grangemouth, Bristol and Manchester Docks.

In general, from this approximate time, most British ports were starting to follow the lead of the shipping Lines and increasing their efforts to accommodate the new techniques. As a result new docking facilities were well on the way to being built around the country. For their part in modernisation the National Dock Labour Board were now running fork lift and platform truck training schools at London, Liverpool, Hull, Southampton Grangemouth, Bristol and Manchester Docks.

To be continued

By James Brindley, Director, National Fork Truck Heritage Centre.

2 Comments

Interesting article, enjoyed reading it!

Very intresting read, i actually learnt a couple of things about our industry